The General Electric Company Porcelain Factory and the U-701

by Ed Sewall

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", January 1998, page 5

The General Electric Company (GE), one of the pioneers of electrical

transmission in this country, was also involved in the manufacturing of some of

the earliest domestic porcelain power pin-type insulators. Unfortunately,

documenting GE insulator production is difficult since there are no known

catalogs. All porcelain insulators produced by GE are thought to have been used

in GE installations, with no known marketing of their insulators. Information in

various trade journals and books as well as documented findings of the product

must be relied upon to try to understand GE's early insulator manufacturing and

installations. Three early, unmarked, dry process porcelain pin type insulators

(U-701, U-744 & U-935A) can be attributed with near certainty to GE. This

article will focus on GE's porcelain factory and the U-701, with a future

article detailing the known installations of the unmarked GE U-744 and U-935A.

According to Tod's 3rd edition of the Porcelain In1ulator Guide Book, GE's

connection to electrical porcelain manufacture dates from 1887 when the Bergman

Electric Company hired a local potter named John Krauss. Krauss began

experimenting with dry process porcelain and then they began manufacture of dry

process pieces for Bergman's use. Bergman Electric was absorbed by Edison

Machine Company in the late 1880's, which became GE. According to Men and Volts,

The Story of General Electric (Hammond 1941), GE moved the Bergman porcelain

operation from 17th Street and Avenue B in New York City to Schenectady in 1889.

William Cermak, a porcelain specialist from Czechoslovakia, ran the porcelain

factory at GE in Schenectady at this time. Cermak is described as having

difficulty producing usable porcelain insulators by the dry-process.

"Experiment after experiment were made, scores of insulators were designed

and tested, only to go to pieces under less than 10,000 volts" (Hammond

1941). Cermak and his engineers are further described producing "the

well-known petticoated insulator which stood the test up to and beyond 10,000

volts". Cermak apparently knew that the dry process units left a lot to be desired. They continued further study and

design in an attempt to make good porcelain insulators for GE's installations.

An understudy of Cermak at this time, Edward M. Hewlett, later became well known

for development of the Hewlett suspension disc insulator in the early 1900's.

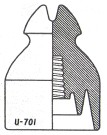

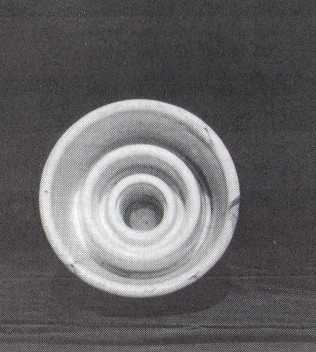

Full view and bottom view of U-701.

Nearly identical descriptions of GE's porcelain factory in Schenectady, New York

are given in articles in The Electrical Engineer dated May 1, 1895 and in

The

Electrical World, dated May 4, 1895. These articles describe the layout of the

small pottery and the manufacture of small dry press items such as sockets,

switch bases, cut-out switches and transformer connector boards. Brief mention

is also made of a small adjoining room where testing of high voltage porcelain

insulators occurred. Although several photographs of the operation are depicted,

this adjoining room is not shown. The articles state that "Among these

(insulators) may be mentioned the large double petticoat insulators for the

important power transmission plant at Folsom-Sacramento". These insulators

were supposedly subjected to a severe test of 25,000 volts alternating, and none

of the insulators gave way until 52,000 volts was applied. It is hard to believe

that any porcelain insulator could stand 52,000 volts in 1895, and this was

probably an exaggeration. The Folsom-Sacramento line mentioned in the factory

description is one of two known sources of the U-701.

The oldest installation

where porcelain pin-type insulators attributed to GE have been located to date

is the Baltic-Taftville, Connecticut line. According to an article in The

Electrical Engineer, dated May 2, 1894, this 2,500 volt DC line was constructed

by the Power and Mining Department of GE for use in supplying power to the

Ponemah Mill, located in Taftville. Conflicting with The Electrical Engineer

description, Men and Volts, The Story of General Electric (Hammond 1941)

describes the installation of an alternating current system in 1893. According

to Hammond (1941), an existing direct current generator installed at Baltic and

direct current motors at Ponemah (Taftville) were apparently proving

unsatisfactory in 1892. As a result they were replaced in late 1893 with new

polyphase alternating current generators and motors produced by the

Thomson-Houston plant of GE. From Hammond's more detailed information, it appears

that this was an alternating current line, possibly one of the earliest

installations of an alternating current transmission line in this country.

The Taftville line was also intended to provide power to the Norwich Street

Railway, although it is unclear if this ever occurred. Although a GE

installation at the Columbia Mills in South Carolina preceded Taftville, this

project was described as the first important use of electrical power

transmission to a textile manufacturer. The Taftville transmission line ran

from a hydro-electric generating station installed in an old rebuilt mill on the

Shetugket River in Baltic, 4.5 miles to Taftville. The transmission line, which

is depicted in a very small photograph (see below), consisted of wooden poles

100 feet apart that were run along the highway and the Shetugket River. The

poles contained two crossarms, each carrying a separate three phase circuit. The

upper line used No. 0 bare copper wire and the second lower crossarm carried No.

0000 insulated wire on four separate lines. The fourth line was installed for

use in case one of the other lines was damaged. The article states that "All

(wires) are supported on the General Electric Company's standard oil

insulators".

Taftville, Connecticut pole line, 1895.

The article also states that "the first motor started two months

ago", inferring that the line started in use in the beginning of March,

1894. Obviously the line was constructed prior to March 1894, with the

insulators also manufactured prior to this date, most likely around the end of

1893 or beginning of 1894.

The reference to GE' s "standard oil

insulators" adds some mystery to this installation as there are no known GE

oil-type insulators. The photograph of the line is low quality and the insulators appear to be

white porcelain, with a poorly defined shape. It is possible that these

insulators could be glass, as white porcelain often looks the same as glass in

many old photos. The U-701 is a white, unmarked dry process insulator with what

is commonly referred to as double petticoats and a shape unlike any other

domestic porcelain insulator. The shape of the insulators on the line are

difficult to discern and can not definitely be identified as the U-701. In the

1970's, a Connecticut collector acquired 4 or 5 of the U-701 insulators that

were previously removed by a lineman from the substation at the Ponemah Mill.

These insulators are assumed to be from the original 1894 installation of this

line.

If the U-701's found in the substation were also used on this line, it is

feasible that they were used with a small oil cup or tray installed underneath

the insulator, possibly explaining the description of an oil type insulator.

However, other than a description of an oil type insulator by Thomas, there is

no evidence that any other domestic companies manufactured a porcelain oil-type

insulator. Additionally, I have not heard of any 701s with oil staining as

would be expected of a relatively porous, dry process insulator sitting in oil.

The insulators depicted on the line could be glass and, although unlikely, may

have been different from those used at the substation. Since the U-701's were

found at this substation originally installed by GE, it makes sense that these

were part of the original installation in 1894. Although the Great Barrington

transmission line in 1893 used porcelain insulators imported from England, it

appears that the installation of the U-701's at Taftville may be the first use

of domestic porcelain pin type insulators used on a domestic power line.

Imperial reportedly manufactured their first double petticoat pin type porcelain

insulators in 1893 (The Electrical Engineer, Aug. 23, 1893), but there are no

known specimens that can be attributed to Imperial's manufacture prior to their

work for Fred Locke in 1895. It is possible that Imperial produced small dry

process pin types for telegraph installations and low voltage use prior to 1895.

Thomas was also making dry process insulators, but probably all small telegraph

styles.

The second and only other known installation of the GE U-701 appears to

be the Sacramento Electric Light & Power Company line between Folsom and

Sacramento, California. This line originated at a hydro-electric power station

located on the American River near Folsom. According to information on file at the Folsom Historical Society and

in an article in The Electrical World (dated April 6, 1895), Westinghouse was

first contacted to bid on the installation. GE got wind of the project and sent

representatives to investigate and bid on the project. GE successfully beat out

Westinghouse for the entire electrical and mechanical installation contract,

signing the contract in September of 1894 and commencing construction in October

of 1894. As appears typical of many early power projects, the company installing

the electrical components provided everything including generators, poles, wire

and insulators.

The power house of the Sacramento Electric Power

and Light Company at Folsom.

Interestingly, The Electrical World article also refers to the "excellent

work done at Taftville" in the beginning of the article. The article

further details the construction of the large dam and hydroelectric plant

using prison labor on the American River at Folsom. Construction of the dam was

completed in 1895 by the Folsom Water Power Company. The dam was used to store

water for irrigation, log storage and for hydro-electric power. The transmission

line, described as 11,000 volts alternating current, was run in duplicate for

20.5 miles from the Folsom power house to Sacramento along the line of the

Sacramento & Placerville Railway and country roads. A total of 2,600, 40 foot,

round cedar poles carried two crossarms, one for each circuit. Each circuit consisted of three bare copper wires supported on

''porcelain

insulators especially designed and made for this installation at the porcelain

factory of the General Electric Company, Schenectady". As described in the

articles detailing GE's factory, each insulator for the Folsom line was

reportedly tested to not less than 25,000 volts alternating, before leaving the

factory.

The Folsom-Sacramento line is also described in the September 1895

issue of The Journal of Electricity. This article similarly describes the

project and includes a photograph depicting the transmission line with four

white porcelain insulators on the top crossarm and two on the bottom crossarm.

As with the Taftville photograph, this photograph is too small to discern the

style of insulator. This photograph also depicts a third crossarm on one of the

pole lines. This lower crossarm carried the telephone lines of the Capitol

Telephone and Telegraph Company.

Double pole line transmission circuits on the Folsom pole line

- Sacramento

Electric Power and Light Company, 1895 -

Several of the U-701's have surfaced in the Folsom and Sacramento areas. Some

of the insulators have been found at flea markets in Sacramento. The most

intriguing find was the discovery of several U-701s near a dumping area in the

Sacramento River. The location of this dump is unknown at this time. The

description of the Folsom-Sacramento insulators (U-701) being specifically

designed for this installation leaves further unanswered questions about the

earlier Taftville line. The Taftville line (alternating current) was installed and in service

by March 1894. The construction work by GE on the Folsom line did not begin

until at least 6 months later (October 1894), and the line and insulators may

have been put in later in 1895 when the project went into service. This raises

several possibilities about the U-701 and its probable dates of installation.

If the U-701 was truly designed for the Folsom line then the most likely

explanation is that U-701' s removed from the Taftville substation were

replacements for an unknown original insulator (the oil-types previously

described?), and were probably installed in late 1894-early 1895. This could

explain the description of the oil-types in the original installation at

Taftville instead of an insulator like the U-701. Another possibility is that

the U-701 was an experimental design initially tested in small quantities in

the substation at Taftville.

Unfortunately, the conflicting descriptions of

these projects and the gaps in the available information lead us to speculation.

The U-701 does appears to be the first power pin type produced by GE, and may be

one of the first porcelain power pieces produced in this country. Very few of

the known specimens of the U-701 would be considered in mint condition. Most

have the fine black cracks and some chipping characteristics of most old dry

process porcelain. Considering the age and short period of time in which the

U-7011 would have been acceptable with quickly increasing voltages, it is

amazing that any of these pieces have survived to this day. The U-701's unique

shape and finely crafted dry process body represent to me one of the most

interesting and collectible classic porcelain pieces. The apparent rarity of the

U-701 (15-20 thought to exist in collectors' hands) as well as its place in the

history of early power transmission definitely make it a classic.

I would like to thank to Steve Jones, Paul Greaves and the Insulator Research

Service for help in researching this article.

References:

The Electrical Engineer, Aug. 23, 1893

The Electrical Engineer, May 2, 1894

The Electrical World, April 6, 1895

The Electrical Engineer, May 1, 1895

The Electrical World,

May 4, 1895 |

The Journal of Electricity, Sept. 1895

Hammond, J.W. 1941. Men and

Volts, The Story of General Electric

Permission granted by Elton Gish for use of U-701 shadow profile.

|